Recently, we published the beta version of the OpenTofu Registry Search, a user interface that lets you search for and view the documentation of providers and modules in the OpenTofu Registry. With this important milestone reached, it is finally time to talk about how the OpenTofu Registry and Search work under the hood and the pitfalls of running a public registry.

The Registry API

OpenTofu and its predecessor Terraform rely on provider binaries created by the community to interact with various APIs. There are currently over 4,000 such providers in the OpenTofu Registry, enabling a wide range of integrations from cloud providers to managing your GitHub account. Anything that has an API to create some kind of resource can be integrated with OpenTofu.

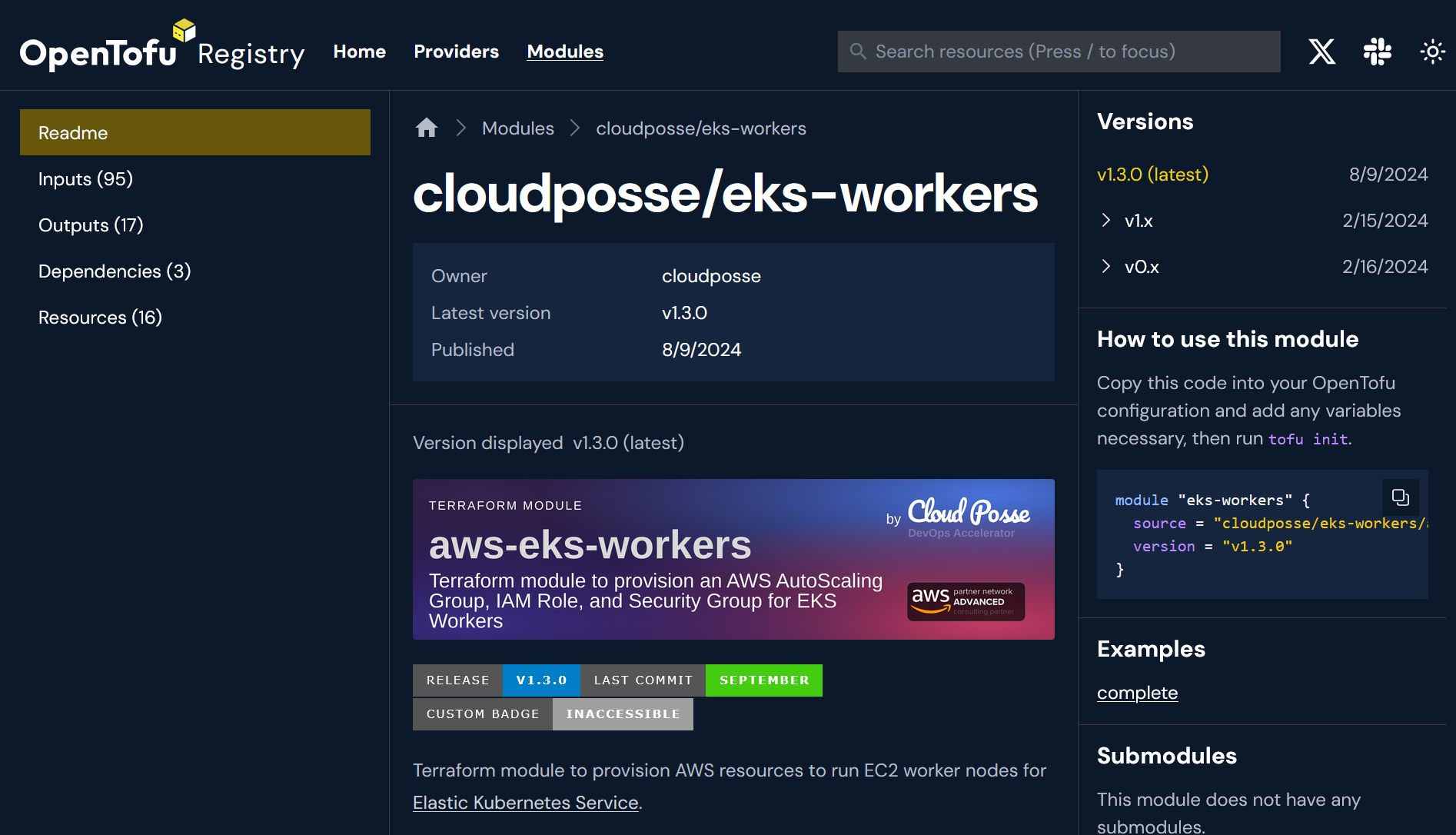

Aside from providers, the community has also created well over 20,000 reusable modules that implement higher level functionality, such as provisioning an entire infrastructure with a cloud provider with only a few configuration options.

Since these providers and modules are created by the community, OpenTofu needs to know where to download them and what versions are available. This is where the Registry comes into play: it holds the information about available providers and modules, download URLs, checksums, and GPG keys for integrity verification.

Step 1: Service Discovery

For both providers and modules, OpenTofu first requests the https://registry.opentofu.org/.well-known/terraform.json file, which has the following content:

{

"modules.v1": "/v1/modules/",

"providers.v1": "/v1/providers/"

}

This file lists the endpoints OpenTofu should query for information about modules and providers. For private registries there is also a third endpoint named login.v1, providing information about an OAuth endpoint to use for authentication. If you are interested in the details, you can read more about this protocol in the OpenTofu documentation.

Step 2: Version Listing

With the endpoint information, OpenTofu can query the version listing endpoint for the desired provider or module.

- For providers this endpoint would be

/v1/providers/NAMESPACE/NAME/versions(example). - For modules it would be

/v1/modules/NAMESPACE/NAME/SYSTEM/versions(example).

Step 3: Download Info

Based on the information received, OpenTofu can request the information about the specific version, operating system and architecture.

- For providers, it would be located at

/v1/providers/NAMESPACE/NAME/VERSION/download/OS/ARCH(example). - For modules, it would be located at

/v1/modules/NAMESPACE/NAME/SYSTEM/VERSION/download(example).

OpenTofu then downloads the provider from the supplied GitHub releases URL and verifies the checksum and signature, or clones the returned Git repository for modules.

Hosting the Registry (for free)

As an open source project with a small core team working on developing OpenTofu itself, it was paramount that we kept the costs of running the Registry as low as possible both in terms of bandwidth and also in human cost. However, we also needed to make sure that the Registry had an uptime close to 100% since thousands upon thousands of developers would be left without a means to update their infrastructure if it went down.

Here we owe a big thanks to Cloudflare. Their very competitive pricing for R2 with no egress fees and their sponsorship of OpenTofu meant that we would be able to run the Registry essentially for free with no servers and scaling issues to worry about. The Registry codebase (written in Go) pre-generates all possible answers of the API above and uploads the static files to an R2 bucket.

Populating the Registry

Alongside the Terraform license change, HashiCorp closed the Terraform Registry for software that isn't Terraform, so using it as a source of data for the OpenTofu Registry was out of the question. However, since the Terraform Registry was coupled exclusively to GitHub, it was relatively straight forward for us to use the GitHub search API to populate the Registry, if a little slow.

Updating the Registry, however, was a much harder problem. GitHub limits the API to ~5,000 requests per hour, which is not enough to update roughly 30,000 providers and modules in a speedy fashion, especially since some updates required multiple requests.

We could have requested provider authors to log in with their GitHub account, granting us an access token we could use for a higher rate limit, but that would have been impractical when we launched the Registry since we would have had to ask thousands of developers to log in at a time when OpenTofu wasn't even released yet.

The solution came by the way of the GitHub RSS feeds, which are not rate limited. The releases RSS located at http://github.com/USERNAME/REPO/releases.atom always contains the last 5 releases, which is sufficient if we only need to add the latest versions as it is unlikely that a provider or module would have more than 5 releases within an hour. For modules, we needed to query the tags instead of the releases, which was even easier because the git ls-remote command gave us all this information and was also not rate limited. (You are going to keep it that way, right, GitHub?)

The submission process

Since we didn't need to ask provider and module authors for their credentials using OAuth, we were able to create a simple submission process that anyone with a GitHub account could use.

While anyone could submit a provider or a module, we still needed provider authors to submit their GPG keys so their binaries could be verified. Instead of asking for OAuth logins, we again decided to use the GitHub API in a creative way. In order to submit a GPG key for a provider, the author needed to set their organization membership to public for the repository of the provider and then submit a GitHub issue. We would verify their membership in the provider organization and process their GPG keys.

Having the submission process being as simple as opening a GitHub issue turned out to be quite popular. To date, the community has opened almost 1,000 pull requests and issues on the Registry repository. It also meant that provider and module authors working for larger organizations did not need to expend any organizational capacity to sign up for an OpenTofu account, resulting in quite a few high profile providers adding their GPG key.

Do you want to learn more about the early days of the OpenTofu Registry? James and Arel from the OpenTofu team held a talk about this topic at the OpenTofu Day at Kubecon 2024.

Building a user interface

After working on the Registry and taking a few months pause for some much-needed work on OpenTofu itself, we returned to building a search and documentation reading interface. As we would soon learn, this was a larger task and resulted in three times the amount of code needing to be written.

As before, we chose an architecture that would generate static files. Early on we had to make a decision between simply generating static HTML files or using a Single Page Application and load the data from an API. We chose the latter because we were concerned that a layout change would require a complete regeneration of all files, which would be cost-prohibitive to upload again and again.

Having made this decision we set out to build a backend and a frontend component, the former being responsible for producing the data the latter would consume. We built libregistry, a standardized Go library that would make it easier to access the metadata stored in the Registry repository and provide a useful abstraction layer on top of GitHub and the various creative API integrations we built to fetch the data.

Pre-processing the documentation

While the Registry always regenerates all API responses from the raw metadata, this approach was not feasible for the documentation due to the sheer volume of data we needed to process. Not only would we have to produce documentation responses for tens of thousands of providers and modules, some of them also had several hundred versions, each of which needed their own copy of the documentation stored.

We decided that we would process the data from the source repositories directly into an R2 bucket without storing any intermediate data. This approach came with its own problems. While the Registry could make use of git to track changes in the intermediate data, we needed to make sure that our uploads to the R2 bucket were as close to atomic as possible so no partial uploads are left behind. While we have implemented a partial solution that can continue an upload, this still remains one of the unsolved issues with the Registry.

In order to simplify the necessary frontend logic for displaying the documentation, the backend's main job is to rename and move each of the documentation files into their standardized place. There is no formalized description on how providers can store their documentation, so the logic for extracting this information is only empirically known. We needed several iterations to work around various bugs as we expanded the number of repositories we ingested and discovered newer and newer edge cases.

Module schemas

While providers typically have their own, explicit documentation, often generated by tools like terraform-docs, modules don't have such information readily available. This makes it difficult to generate information about their inputs, outputs and dependencies.

HashiCorp published terraform-schema for extracting this information, duplicating some of the module parsing logic from Terraform. However, we decided that maintaining duplicated codebases would likely cause a maintenance issue down the line and implemented this functionality directly into OpenTofu. This patch currently lives on a branch, but will be integrated into the main branch as an experimental feature at a later date.

Licenses

During the ingestion process we also needed to concern ourselves with licenses: as we were unsure under what legal standard such a documentation dataset would fall, we deliberately chose a restricted set of licenses that we would accept into the Registry documentation. We performed automatic license detection on each provider and module repository to avoid ingesting content under potentially problematic licenses.

The OpenTofu Docs API (and how you can use it)

Doing all this work on the backend and splitting the display logic from the data also had an unintended but very welcomed side effect: we were able to offer an API for provider and module documentation, which would come in handy as just a few weeks later Jetbrains requested just such an API for their OpenTofu integration.

The backend produces the dataset in this format and is easily runnable locally from the registry-ui repository, while the public API is available for anyone to build integrations with. We even made sure to include the correct CORS headers if you would like to build a browser-only integration. If you build something cool with it, let us know!

Search

As we were building the backend, one issue was constantly on our minds: how do we make such a vast data set searchable? We hoped that it would be possible to simply generate a search index and let the client JavaScript deal with the entire search problem. As we were looking at lunr.js, a robust and mature library for search, it quickly became apparent that this path would be entirely unfeasible. Even with a limited data set, the download size of the search index quickly ballooned to several hundred megabytes, which is not exactly ideal for a snappy search functionality not to mention really upsetting to people with data caps.

Not wanting to run our own database server or involve any more service dependencies, we looked at Cloudflare's D1, a SQLite database service and a worker to handle search queries. While it initially looked promising, we discovered that we would have to submit all updates in a single HTTP request in order to run them in a transaction.

It would have been possible to work around it and still perform atomic search index updates, but we ended up using Neon, a database-as-a-service offering, instead. They don't explicitly sponsor OpenTofu, but their free tier was comfortably enough for our search index and the next tier was also quite affordable. Their tight integration with Cloudflare was also a very welcome addition.

To query the database hosted at Neon, we created a Cloudflare worker. This worker ended up handling all requests to api.opentofu.org, forwarding the static requests to R2 and handling the search queries itself.

The backend would prepare a line-delimited JSON (ndjson) file with a data feed at https://api.opentofu.org/registry/docs/search.ndjson, containing all recent updates to the search index that the worker could ingest and fill into the database.

Where do we go from here?

The OpenTofu Registry Search is currently in beta, indicating that not everything is working yet. As we are expanding the amount of providers and modules indexed, we will certainly discover more edge cases that need to be fixed.

The libregistry library also duplicates a lot of the functionality present in the registry codebase as well. We want to deduplicate this functionality, both for long-term maintenance and because libregistry would make it easier for people to run their own mirror or even independent copy of the Registry.

During this process your feedback is invaluable for prioritization. If you find a bug or have a use case we haven't considered, please use GitHub issues to let us know.